by Kayla

For those of you who don’t know me, I am a woman of many hats at France 44. I work with the Beer Team, and I’m 100% that woman who, on day two or three knew your name, your dog’s name, and the name of one of your family members. My strengths in the beer world come from being a member of Witch Hunt Minneapolis, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that works for gender equity in craft beer brewing through education. My experiences with them gave me brewhouse experience from Barrel Theory, Arbeiter, and BlackStack. I have training with Better Beer Society and am also continuing my education with the Cicerone program.

Today we’re talking about bacteria in beer–the good kind, the kind that started those old-school, natural-beauty versions of sour beers. I’m talking about Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, and Acetobacter. Trust me, bacteria in beer at the appropriate amount is a very good thing.

Pediococcus. This is the slow poke bacteria of the beer world, and it takes a LONG time for it to get started. On the plus side, it allows time for the primary yeast to complete fermentation so there’s no need for dismissal quite yet. However, this bacteria is also kind of high-maintenance: too much and your beer will taste like diacetyl (commonly known as ‘movie theater popcorn butter’). Therefore, it does much better with a friend like Brettanomyces in order to help lower the final level in your beer. Once in control, it produces deliciously funky aromas and flavors.

Lactobacillus. This bacteria is responsible for converting sugars in the word (pronounced wert) to lactic acid. It’s responsible for the level of sour in the beer, but also for giving it a clean taste. You can call it the “second in command” under Saccharomyces. Lactobacillus can also be found in foods like kimchi and yogurt.

Your challenge, should you choose to accept it, is to look in France 44’s Imported Beer section and give some of these unique beers a try. Most of them are only offered in a single bottle, and you’ll definitely be surprised.

Acetobacter. Finally, Acetobacter is a not-so-common bacteria in the beer world. It’s know as the “silent but deadly” bacteria: it consumes ethanol to produce harsh-tasting acetic acid, which means that a little bit of this guy really goes a long way. This is also why once you use it, you have to pitch it and clean your equipment well in order to keep this bacteria from attaching itself onto any tank or tool used. Acetobacter is responsible for Flemish reds and Belgian Lambics.

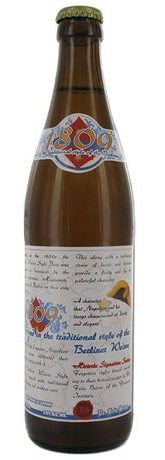

PROFESSOR FRITZ BRIEM’S 1809 BERLINER WEISSE from Freising, Germany uses lactic acid, which is produced by Lactobacillus and Pediococcus. Berliner Weisse beers are also known as “The Champagne of the North.” Some people use sweet syrups in this style of beer but I like them as natural as they get, like this example. At 5% ABV, it is fermented in traditional open fermenters, giving it complex fruitiness and tartness.

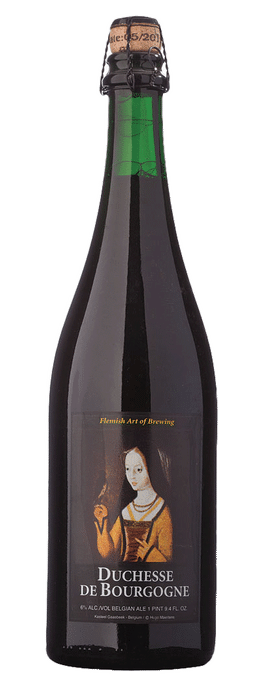

DUCHESSE DE BOURGOGNE from Verhaeghe Brewing in Vichte, Belgium, is a Flemish red that uses Acetobacter. It has a dry, acetic finish that complements the passionfruit and chocolate notes in the beer. After the first and secondary fermentation, this beer goes into oak barrels for 18 months and comes out at 6.2% ABV.

CROOKED STAVE SOUR ROSÉ is a mixed culture beer, with raspberries and blueberries and fermented in oak foeders. It is naturally wild, but the effervescent character gives it a rosé-like personality. And at 4.5% ABV, you can definitely have more than one.