Wine #1: William Fevre “Champs Royaux” Chablis

SIGHT: This sprightly young wine is Chardonnay at its most straightforward. The color is a barely-there, watery-hued lemon color with the faintest tinge of green. This is a great indication of little to no oak or age, and the lack of thick tears going down the side of the glass tells us this is probably not a wine with high alcohol content—therefore coming from a cool region, like Chablis!

SMELL: Cut open a fresh lemon, peach, and green apple to see if you get similar notes in this wine. Any other citrus or orchard fruits come to mind? After digging beneath those initial fruit aromas, see if you can detect any mineral or smoky elements—maybe wet stone, a little matchstick, or a touch of paraffin wax?

TASTE: This wine has a medium-light body, medium-high acidity (feel the tartness in your cheeks?) and medium alcohol. These structural components are what make this style of Chardonnay one of the most reliable and flexible food pairing wines. Hints of sweet lemon, green apple skin, pear, and maybe a little green Jolly Rancher dance around on your tongue before disappearing with a fresh burst of acidity. The area of Chablis in France is famous for its chalky, limestone and special clay soil. The soil type and the cool climate are the major factors in the character of this zippy, linear style of Chardonnay.

Notice how “green-fruited” or fresh this Chardonnay smelled and tasted! The wine was not aged in oak, and it didn’t go through malolactic fermentation (“malo”), which is the conversion of harsh, lip-puckering malic acid to softer, rounder lactic acid (this process is how Chardonnay can seem “buttery” sometimes). Therefore it’s crisp, clean, and pretty lightweight. Also, notice the alcohol level: a very modest 12.5%. This will be important to note as we get to know the next two wines. So, now that we know what a “bare bones” Chardonnay is like, we can start adding some layers to it! Onto the next wine…

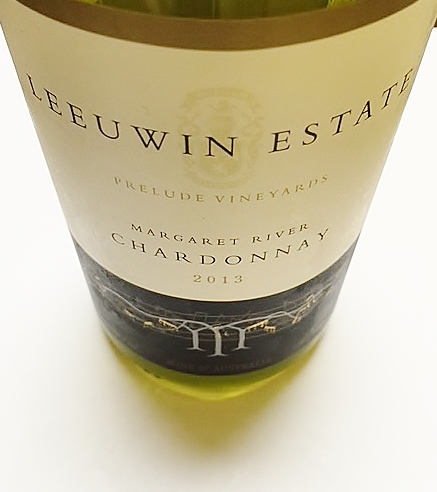

Wine #2: Leeuwin Estate “Prelude Vineyard” Chardonnay

SIGHT: The color of this wine is fairly similar to the Chablis, with maybe just a touch more intensity at the core. This is a pretty good clue that we’re sticking with a moderate to cool climate.

SMELL: Throw a piece of bread in the toaster and take out your bottle of vanilla extract and see if there are similar aromas in this wine. The first bunch of smells you’ll probably get is secondary aromas, which are (if you remember from the previous Deconstruction) basically anything other than fruit. These aromas come out when the winemaker has manipulated the wine in some way—in this case, by using wood aging and malo. Oak, vanilla, various baking spices, crème brulee, or maybe even mineral or plastic notes could come through.

TASTE: Due to the oak and malo used on this wine, the body here is slightly fuller than the Chablis; the texture has a plush softness to it, and the fruit has a riper quality to it. Flavors reminiscent of Red Delicious apple—maybe even spiced apple cider—along with a faint bitter lemon peel quality on the finish keep this Chardonnay zesty and fresh, even though the oak dominates. We can say this wine has a medium-full body, medium to medium-plus acidity, medium alcohol (13.5%–a full point more than the Chablis) and a finish that is medium-plus in length.

Leeuwin Estate is one of the most important estates for Chardonnay in Australia. Leading the way in the 1970s and 80s, they were responsible for showing the rest of the world that quality Chardonnay could be made even in an upside-down country like Australia. Margaret River in southwestern Australia, where Leeuwin is located, is many times referred to as “the Bordeaux of Australia” because of its similar climate and rocky, alluvial soils that provide wonderful drainage for the grapevines. And although we might think of Australia as a hot, desolate, arid country, Margaret River is one of the most temperate climates in the Southern Hemisphere. This is a great example of a wine with decently high acidity but also with a significant amount of oak.

Wine #3: Paro Chardonnay

SIGHT: Pure gold! The intensity of this deep, rich Chardonnay makes the first two wines look like water. Just by looking at this popcorn-butter-yellow hue, we know we’re in for a massive wine.

SMELL: I don’t know about you, but I get all the food groups in this wine: butterscotch, mushy yellow apple, lemon meringue pie, pear skin, buttered popcorn, and definitely melting vanilla ice cream. (That covers the whole pyramid, right?) This Chardonnay is luscious to the core. The fruit aromas aren’t crisp and fresh—they’re overripe, baked, and sautéed. Again, this is a great example of how much effect climate has on a singular varietal. Go back to the Chablis for a second: can you believe these two wines are the same grape?!

TASTE: There’s no end in sight to this wine! Full-bodied with medium-plus alcohol (this guy is a whopping 14.5%–more than a lot of red wines!), it has medium to (maybe) medium-plus acidity but definitely a long finish. Silky, luscious and rich on the tongue, this wine has potential notes of butterscotch, applesauce, vanilla, and honey graham cracker. Remember, the name of the game is to connect elements of your wine with tangible things in everyday life: dig through your fridge, pantry and cupboards to find familiar smells and tastes so you can further connect to what’s in your glass.

The Russian River Valley of Sonoma in California is one of the best-known places for its cool climate Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Early morning coastal fog blankets vineyards, providing cool temperatures throughout most of the day and night except for a few hours of essential sunshine during the warm afternoons. This vital phenomenon is called the diurnal shift: the range of the high temperature of the day to the low. The greater the range, the more complex, balanced, and ripe the grapes become. That being said, there are clearly still parts of the inland Russian River Valley warm enough to produce wines of high alcohol content, like this Chardonnay from Paro. This element, combined with New World wine producers’ infatuation with new oak and full-on malo, result in this wine—the furthest thing from our initial French Chardonnay introduction.

Clearly, New World Chardonnay is pretty far removed from the Old World style. Even when oak is used in French Chardonnay, it’s usually much more subtle and isn’t meant to be used as a flavor. California winemakers have latched on to American wine drinkers’ obsession for those luxurious butterscotchy, oaky, toasty, vanilla-y notes in their Chardonnay, and they’ve perfected their signature style. And once again, climate is one of the most important factors!

But really, why stop with just still Chardonnay? As we’ve already discussed, Chardonnay is incredibly versatile in the jobs it can accomplish around the globe. It’s high time we discovered the other different forms this world-class grape can take! Tune in soon for a dive into the effervescent side of Chardonnay, and learn about the bizarre way it came into being. Cheers!