Jennifer Simonson

Jennifer is a writer, photographer and wine enthusiast who publishes a blog called Bookworm, in which she pairs wine with books. It combines two of her favorite pastimes and is intended to make both reading and sipping wine more enjoyable. She recently received her WSET Level 3 in Wines certification through France 44 Wine & Spirits Education. She lives in Linden Hills and enjoys running around the city lakes, gardening, cooking and making art.

I recently tasted one of France 44’s popular summer wines, Amity Vineyards White Pinot Noir from Oregon’s Willamette Valley. The wine is deliciously refreshing, but it’s unusual because it is a still white wine made from red-skinned grapes. As a result, expect a fuller mouthfeel than many warm-weather whites, and a wide array of aromas and flavors. I noticed white blossoms, ripe white peach, tangerine, and white cherry.

(For a special treat, follow cheesemonger Sophia’s recommendation and pair it with nutty and sweet Ossau-Iraty, a sheep’s milk cheese from France’s Basque region.)

The tasting experience sparked my curiosity about unconventional winemaking practices; specifically, handling red grapes like white ones in the winery, and white grapes more like red. So, let’s return to our White Pinot Noir.

Nearly any red-skinned grape can be used to make white wine because the pulp inside is pale green. (Red-fleshed teinturier grapes, like Alicante Bouschet or Saperavi, are an exception). The grape skins give wine its color, so limiting their contact with the juice prevents the wine from turning red.

To do this, grapes are hand-harvested, ideally under cool conditions, and carefully rushed to the winery. A quick and gentle press, sometimes in whole bunches, separates the juice from the skins. And then, just like any other white wine, it undergoes a cool and slow fermentation. Thin-skinned grapes like Pinot Noir work best, as do Gamay, Grenache, and Sangiovese, but most important is the balance between acidity and flavor development. Wines made in this style are delightfully crisp and vibrant, with hints of red fruit, but have a textured mouthfeel.

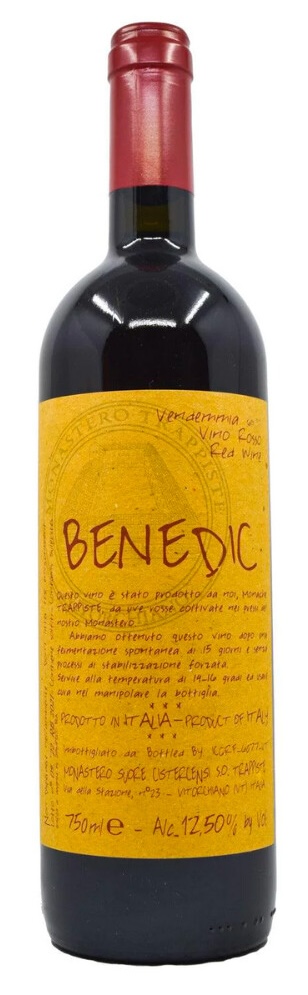

Conversely, some winemakers apply red winemaking techniques to white grapes, keeping juice in contact with the skins and seeds to extract color, flavor, and tannin. The result is orange wine, sometimes called amber or skin-contact wine.

These wines are nothing like those discussed earlier, but they’re still perfect for the summery days ahead and pair beautifully with a variety of foods. Interesting and complex, orange wines have bold aromas, deep flavors, and tannic structure. The juice can macerate and ferment with the skins and seeds anywhere from a day to an entire year. Some undergo further aging in neutral oak barrels or in bottle. Rather than tart citrus or tangy fruit notes, expect dried flowers and dried stone fruit, depending on grape variety, length of skin contact, and type of fermentation vessel.

Skin-contact white winemaking is an ancient practice, likely originating in the Republic of Georgia, but now popular worldwide. Because tannin helps preserve wine, many orange wines have little or no added sulfur and are considered natural wines.

Not a bright white nor an intense red, orange wines occupy the space in between. Serve them at 55-63 F, cellar to cool room temperature, unless the bottle specifies otherwise. If too cold, the wine will taste bitter and astringent, and the aromas will be muted. Orange wines are incredibly food-friendly and pair well with cheeses and cured meats, spicy or earthy vegetarian dishes, fish, and lean meat.

Skin contact, or lack thereof, allows winemakers to showcase alternate expressions of familiar grapes. While neither of these winemaking practices is new, they both provide curious wine enthusiasts like ourselves a range of interesting, and somewhat unexpected, flavors and aromas to explore.