by Sam Weisberg

Gather round, all ye of hardy constitution and eccentric drinking habits! ‘Twas the week before Halloween when Sam wrote a blog post about Genever; that elusive spirit of cocktail-lore, long figured to be lost to history. It’s a tale of an ingredient coming back from the dead, the resurrection of the crown jewel of the Cocktail Renaissance.

Editor’s Note: We’re gonna be nerdy and go through some history here. If you want to just know what the stuff tastes like, skip to the bottom of the article, or come visit us at the store this weekend—we’ll be pouring Old Duff Genever on the tasting bar.

Prologue: Minnesota, 1867

It’s 1867 and you’ve had a long, hard day farming sugar beets in Winona. You head over to your local watering hole, and, perhaps being a somewhat well-to-do farmer, you treat yourself and ask the bartender for a “gin cocktail.”

What you receive in your chilled cocktail glass is not a Martini. It’s not a gin-and-tonic, and, smelling it, it’s not even particularly piney or juniper-forward. You take a sip of the light-amber hued concoction… what you taste is not unlike an Old-Fashioned; there’s definitely sugar, definitely some sort of cocktail bitters, but that base spirit… it ain’t gin.

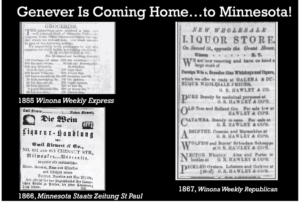

And that’s because it wasn’t gin. Or, at least, not what we’d consider gin today. The spirit—which you can see advertised here in the Winona Weekly Republican was called “Holland gin”—or, as they called it in Holland, genever.

The Long Road to Gin

Genever is old. Really old. Descended from medicinal juniper tonics that were being produced as early as 1269 CE, genever has been taxed as a recreational spirit in Holland since 1497! It is the parent spirit of both whiskey and gin, a fact that quickly becomes apparent after your first sip. Malty and rich, yet lightly flavored , genever is like the love-child of single malt scotch and English gin.

The earliest Irish whiskey recipes, dating from 1611, were for unaged, well-crafted grain distillate with a teensy amount of botanicals added for flavor, including juniper. That’s essentially a description of genever. The real stuff, what the Dutch would have called moutwijn, or, maltwine, is a distillate of grains (traditionally malted barley and rye—more on that in minute) with a small amount of juniper and hops (!) added for flavor.

That traditional style maltwine genever swept the (European-influenced) globe, at times becoming even more fashionable and expensive than Cognac. By the mid-1860s, genever was one of the world’s best-selling spirits—popular enough that it was even being shipped out to the fledgling Northwest Territory of the U.S., which would soon become Minnesota (see the 1855 ad above in the Winona Weekly Express).

While Americans stuck to imported Dutch Genever (imports to New York in 1850 dwarfed English gin at a ratio of 450:1), the British attempted to make their own version of it. Unfortunately, British distillers couldn’t compete with the technique of the Dutch masters. To cover the harsher base spirit that many distillers produced, merchants would often sweeten the spirit with sugar and add additional juniper flavor. The resulting spirit is a poor facsimile of genever, but it became quite popular with the British public, who dropped the “-ever” and called it “gen,” which quickly transformed into “gin.”

That sweetened style of gin was known as “Old Tom” gin—and you can still purchase it today from a select few producers. For a time, true Dutch genever and Old Tom gin were interchangeable in the bartender’s arsenal, with the former taking the name “Hollands” in many recipe books. Up until Prohibition in the U.S., if you asked for gin in a bar, you’d probably be getting either genever or Old Tom.

It wasn’t until the invention of the column still in the early-1800s that anything resembling the “dry gin” we know now began to come onto the scene. The spirit produced by a column still was lighter and crisper than the malty, fuller-bodied stuff that came off the old-school pot stills used to make genever. Column-stills also produced spirits with fewer impurities, allowing producers to bottle it with less and less sugar to cover up “off” flavors.

Real Dutch genever began a slow decline in popularity due to the dual tragedies of American Prohibition and World War I, but after the devastation of World War II, Dutch producers had to decisively pivot away from it to survive. The techniques of genever production were labor-intensive and the raw materials were expensive. Sensing a changing marketplace and a need for fast cash, Dutch producers went all-in on liqueurs and vodka for their export markets. Some distillers continued producing a bit of genever for local tastes, but the marketplace had changed—today, only a dozen or so distilleries remain in Schiedam, the historic home of genever production—down from the industry’s peak of about 250 distilleries in its heyday.

Enter the Duff

The revitalization of pre-Prohibition cocktail recipes and techniques that has swept the U.S. over the past twenty to thirty years has been called the “Cocktail Renaissance.” History buffs, academics, professional bartenders, and at-home tipplers have all contributed to a wealth of information that has allowed bars to slowly but surely shift drinking culture in the U.S. back towards spirit-forward cocktails with high-quality ingredients. In other words: Negronis are in, Sour Mix is out.

Key to this transition has been the resurrection of (formerly) archaic ingredients like absinthe, rye whiskey, vermouth, and, now, genever, which were called for frequently in pre-Prohibition cocktail recipes, but, until recently, were mostly unavailable in the United States. Enter Philip Duff, a cocktail soothsayer who was on a single-minded mission to bring back genever. And not just any genever, but a true, 100% Maltwine.

See, genever production hadn’t exactly stopped cold in Holland following the post-WW2 market crash; a few Dutch producers like Bols had continued to keep it in their product lines. But the product they were making, sometimes called jonge genever or “young” genever, was a column-still product that didn’t really resemble the old-school stuff. It was lighter in flavor, more juniper forward, and, critically, the base spirit was not the traditional moutwijn blend of malt and rye, but a neutral grain spirit—more like a vodka.

Philip Duff set out to rectify this. Approaching a historic distillery in Schiedam with a historic genever recipe in hand, he contracted them to produce Old Duff Genever: a true Dutch genever with the historic seal of Schiedam (they’ve got a seal for everything over there) on the bottle, certifying it as the real-deal thing.

What the Heck Does it Taste Like

Old Duff comes in two varieties:

The green bottle Old Duff Genever ($36.99) is a modern-style genever. 53% pot-still Maltwine, 46% column-still wheat distillate. The column-still spirit lends a lighter touch to this bottling, which, combined with a broader botanical base that includes juniper, citrus, coriander, star anise, and licorice, creates a sip that tastes like a fuller-bodied, maltier style of London Dry gin.

This is the stuff to pull out for a party. Make long drinks like a John Collins (John for jenever!) with it, or sub it out for gin in a cold-weather G&T. Bottled at 40% ABV, it’s meant as an approachable first sip into the world of genever.

Old Duff’s black-label, 100% Maltwine ($49.99) on the other hand, is the real-deal genever experience. This is what genever would have tasted like in the 1800s. Made from 2/3rds rye and 1/3rd malted barley, and flavored with only juniper and English bramling hops, this authentic moutwijn is the missing ingredient in dozens upon dozens of classic American cocktails. It’s the missing link between scotch and gin, the middle-ground when you don’t know if you want whiskey on the rocks or a Martini.

Mix yourself up a Martinez, the predecessor of the Martini, with Old Duff instead of gin and sit back in bliss. Or try an Improved Gin Cocktail—essentially a genever old-fashioned—and learn what contentment is. The stuff is magic, and its ability to bring lost cocktails back from the dead is truly a Halloween miracle.

…

Our friends at Libation Project will be mixing up genever cocktails on the bar this weekend at France 44. Swing by to have a little taste of history, and then pick up a bottle or two for yourself so you can take your own crack at a little liquid necromancy this Halloween season. Proost!